Current Concept Review

Differentiating Between Septic Arthritis and Lyme Arthritis in the Pediatric Population

1Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY; 2Stony Brook University Hospital, Department of Orthopaedics, Stony Brook, NY

Correspondence: Carlos D. Ortiz, BA, Stony Brook Renaissance School of Medicine, 100 Nicolls Road, Stony Brook, NY 11794. E-mail: [email protected]

Received: April 10, 2023; Accepted: June 9, 2023; Published: August 1, 2023

Volume 5, Number 3, August 2023

Abstract

Septic arthritis and Lyme arthritis are two conditions that can present with similar symptoms, making it challenging to differentiate between them in a clinical setting. While septic arthritis often requires immediate surgical intervention, Lyme arthritis can often be managed effectively with antibiotic therapy alone. However, given the dangerous nature of untreated septic arthritis, accurate diagnosis and timely intervention are crucial in managing the condition, especially in the pediatric population. Efforts to distinguish between the two conditions include the use of laboratory tests, history and physical exam findings, and MRI imaging. The authors aim to explore the causes, presentation, and treatment of septic versus Lyme arthritis as well as to provide a summary of the evolving research in this area and propose an algorithm that can aid in diagnosis. By synthesizing the proposed algorithm in diagnosis, clinicians will be better equipped to manage septic versus Lyme arthritis effectively while avoiding invasive procedures such as joint aspiration.

Key Concepts

- Septic arthritis is a medical urgency that requires prompt diagnosis and treatment to achieve positive clinical outcomes.

- Arthritis is a late-stage symptom of Lyme disease that can be challenging to distinguish from septic arthritis.

- Laboratory tests, a thorough history & physical exam, and MRI imaging can aid in diagnosis and help clinicians manage these conditions without resorting to invasive procedures like arthrocentesis.

- While septic arthritis usually requires joint drainage, Lyme arthritis can be managed effectively with antibiotic therapy.

Introduction

Septic arthritis is a medical emergency that carries serious consequences if not diagnosed early and treated effectively. Patients with a suspected case of septic arthritis are required to undergo prompt arthrocentesis and when confirmed, usually require debridement of the affected joint followed by a prescribed course of antibiotics.1 Lyme arthritis is a late-stage symptom that manifests in Lyme disease, a multisystemic disease caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi and is the most common vector-borne illness transmitted by a tick bite.2 Although Lyme arthritis presents similarly to septic arthritis, Lyme arthritis may be treated with the use of antibiotics and without the need for surgically invasive procedures.3

Distinguishing between septic arthritis and Lyme arthritis has been a challenge in the clinical setting due to the significant overlap in presenting symptoms observed in both conditions.1,4 This review discusses the causes, presentation, and treatment of both conditions along with important research that has been produced to help guide clinical diagnosis.

Septic Arthritis

Septic arthritis is more common in boys than girls with a ratio of 2:1, with an incidence in developed countries ranging from 4 to 5 cases per 100,000 children per year.5 The most affected joints in septic arthritis are the larger joints of the lower limbs, including the hip, knee, and ankle joints.5

Methicillin-sensitive and resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus are the most common cause of septic arthritis and community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) as an isolate in 26%-63% of cases of septic arthritis.1 Some strains of CA-MRSA produce the cytotoxin Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), which is associated with more complex infections involving higher rates of septic shock, longer hospital stays, a greater number of surgical interventions, and extended antibiotic therapy.6 CA-MRSA may be associated with deep vein thrombosis, septic emboli, or multisystem organ failure.

Other common causes of septic arthritis include Kingella kingae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Enterobacter, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Neonates are susceptible to infections caused by Streptococcus agalactiae and gram-negative enteric organisms such as Escherichia coli. Haemophilus influenzae renders unvaccinated pediatric patients vulnerable to infection. Patients with sickle cell disease are at risk for developing septic arthritis caused by encapsulated organisms such as Salmonella spp. and Neisseria Meningitidis.1,7 Sexually active adolescents are at risk for Neisseria Gonorrhoeae as the causative agent.8

Pathophysiology

Most cases of septic arthritis are due to joint infection because of hematogenous inoculation through the transphyseal vessels, which cross the growth plate (physis) and provide a connection between the metaphysis and the epiphysis and subsequently into the joint lumen.1 Infection can also spread due to adjacent osteomyelitis or by direct inoculation from trauma or surgery.7

The inflammatory response to the bacterial infection in the joint produces high local cytokine concentrations, which then increase the release of matrix metalloproteinases and other collagen degrading enzymes that deteriorate the tissue in the joint space. Bacterial toxins and lysosomal enzymes further damage articular surfaces. Joint destruction can begin as soon as 8 hours following inoculation.1 Additionally, an increase in intracapsular pressure in the hip joint may lead to compressive ischemia and avascular necrosis of the femoral head if not addressed promptly.7

Diagnosis

Patients with septic arthritis typically present with an acute onset of joint pain with limited movement and fever. Peripheral joints may be red and swollen, yet joint effusion can be difficult to detect in the hip and shoulder without advanced imaging (US/MRI). Some conditions can present similarly and include trauma/hemarthrosis, inflammatory arthritis, tumor, leukemia, Henoch-Schonlein purpura, sickle cell anemia, transient synovitis, and arthritic Lyme disease. Many of these conditions can be excluded radiographically; however, a number of these conditions are more difficult to differentiate due to significant overlap in clinical presentation, for example, arthritic Lyme disease.4,9

Laboratory tests can guide the differential diagnosis and include a complete blood count (CBC) with differential, C reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and blood cultures.7 A commonly quoted scenario informs that a serum white cell count (WCC) greater than 12.0 × 109 cells/L showing greater than 80% neutrophils, an ESR greater than 40 mm/hr, and a CRP greater than 20 mg/L are significantly more common in septic hip arthritis in comparison to transient synovitis. Although important, laboratory tests should not be solely relied upon in making a definitive diagnosis of septic arthritis, as some causes of mono-arthritis may yield similar test results such as those seen in Lyme arthritis.10 Radiographs of the involved joint can rule out fractures and other conditions.4 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be needed to determine the extent of the infection and determine if there is concurrent myositis or osteomyelitis.

An ultrasound of the affected joint is the most sensitive test for detecting joint effusion seen in septic arthritis and can assist in aspiration.1,7 When indicated, synovial fluid sample is evaluated with a cell count, Gram stain, culture, and sensitivities (MCS). A synovial fluid WCC greater than 50 × 109 cells/L with a neutrophil (PMN) dominance of > 90% is often used to differentiate identify septic arthritis. Gram stain confirms the diagnosis but may only be positive in one-third of cases.7 Antibiotics are often withheld in medically stable children until a synovial fluid sample is obtained. Yet, in obvious sepsis and the potential for hemodynamic instability, it is prudent to begin antibiotics as soon as possible.

Treatment

After synovial fluid sample and blood cultures are collected, empirical antibiotics (IV) are started based upon suspected pathogen, and antibiotics are adjusted accordingly when MCS are known; patients are transitioned to oral antibiotic when appropriate. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDs) can aid in pain relief and fever reduction. A 4-day course of low-dose dexamethasone can also provide symptomatic relief and lead to earlier clinical and laboratory improvement.7,11

In some cases, surgical intervention is recommended. The surgical management of septic arthritis is urgent decompression of the joint via an arthroscopy, open arthrotomy, irrigation, and debridement.1,7 Before discharge, the child’s healthcare team must verify that the child is tolerating the oral antibiotic and that the parents are well informed about the importance of regular dosing. Ongoing follow-up may be suggested to monitor for long-term sequelae of septic arthritis such as cartilage damage, growth disturbance due to growth plate damage, and avascular necrosis to the femoral head.7,11

Lyme Arthritis

Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne illness (the spirochete Borrelia Burgdorferi) and is endemic in the Northeast and the Midwest where heavily wooded terrain serves as the habitat for the Ixodes tick. Nearly 80% of cases are reported between May and August, with the highest incidence occurring in children 5-9 years old.10

Pathophysiology

Lyme disease is a multisystemic disease that commonly progresses through early and late phases with symptoms that present in a typical pattern.3,10,12 The early phase of Lyme disease is characterized by constitutional, flu-like symptoms accompanied by erythema chronicum migrans, known as the hallmark "bullseye" rash. Fewer than half of patients present in the clinic with early-phase symptoms and even fewer recall ever being bit by a tick. The later phase of Lyme disease comprises neurological (more common in adults) and oligoarticular arthritis (common in children), especially involving the knee.10

Diagnosis

A pediatric patient with Lyme arthritis may have an acute presentation of low-grade fever and monoarthritis most commonly affecting the knee although other large and small joints can be affected. Affected joints may be warm and have very large effusions with limited pain.3

There is significant overlap in the clinical, laboratory, and many radiographic findings of children with Lyme arthritis and septic arthritis.2 Standard laboratory tests might show elevated ESR, elevated creatinine phosphate, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and hepatic transaminase levels.13 It is not uncommon for a patient with arthritis to present with symptoms similar to that from a patient with septic arthritis and a synovial joint aspirate is performed. Patients who are eventually diagnosed with Lyme arthritis have joint fluid, which is usually cloudy yellow and with cell counts below 50,000 white blood cells and with a negative Gram stain. Even when the aspirate is less concerning for bacterial infection and the clinical suspicion for Lyme arthritis is high, many centers will recommend broad-spectrum antibiotics until the cultures come back negative for bacteria.

Currently, a two-step serological testing is the cornerstone for diagnosing Lyme arthritis and include an initial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) followed by a confirmatory Western blot. Detection of IgG and IgM against the spirochete Borrelia Burgdorferi will confirm exposure to this pathogen. False negative test results may be possible if seroconversion has not yet occurred, which may take up to 8 weeks.14 False positive results may occur as a result of cross-reactions with other diseases such as Syphilis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and Systemic Lupus erythematosus.12

Treatment

Treatment for Lyme arthritis requires antibiotics, most commonly doxycycline, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, or other second and third generation cephalosporins. Most cases resolve after the recommended initial treatment of a 30-day course of doxycycline or amoxicillin. However, some patients may experience persistent joint pain despite taking oral antibiotics, in which case IV ceftriaxone may be recommended for 2-4 weeks. Although rare, some patients may experience persistent arthritis for months or years after treatment with antibiotics. These patients may be treated with anti-inflammatory agents, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), or synovectomy.3

Differentiating Septic Arthritis from Lyme Arthritis

Many inflammatory markers (CRP, ESR, and synovial fluid WBC count) that are elevated in septic arthritis are also elevated in Lyme arthritis. As previously mentioned, a synovial fluid sample WBC count > 50 × 109 cells/L has been utilized to guide in the diagnosis of septic arthritis; however, recent studies have shown synovial WBC counts in excess of 50 × 109 cells/L to be quite common in Lyme arthritis.9,10 However, one study by Cruz et al.4 analyzed synovial WBC counts in cases of pediatric hip pain and observed no overlap in the 95% confidence intervals between septic and Lyme arthritis. The authors propose utilizing the upper end of the 95% CI (65 × 109 cells/L) as a potential cutoff. Values above this can be strongly suggestive of septic arthritis. We believe that a patient with an elevated ESR ≥ 40 and a synovial WBC count > 65 × 109 would likely point towards bacterial septic arthritis; yet this clinical algorithm has yet to be prospectively validated.

Several studies have been conducted to help distinguish septic arthritis from Lyme arthritis. One such study suggests that Lyme arthritis tends to present acutely in children, with on average less than 2 weeks of symptoms before evaluation compared to adults who report having symptoms for over 6 weeks before evaluation.

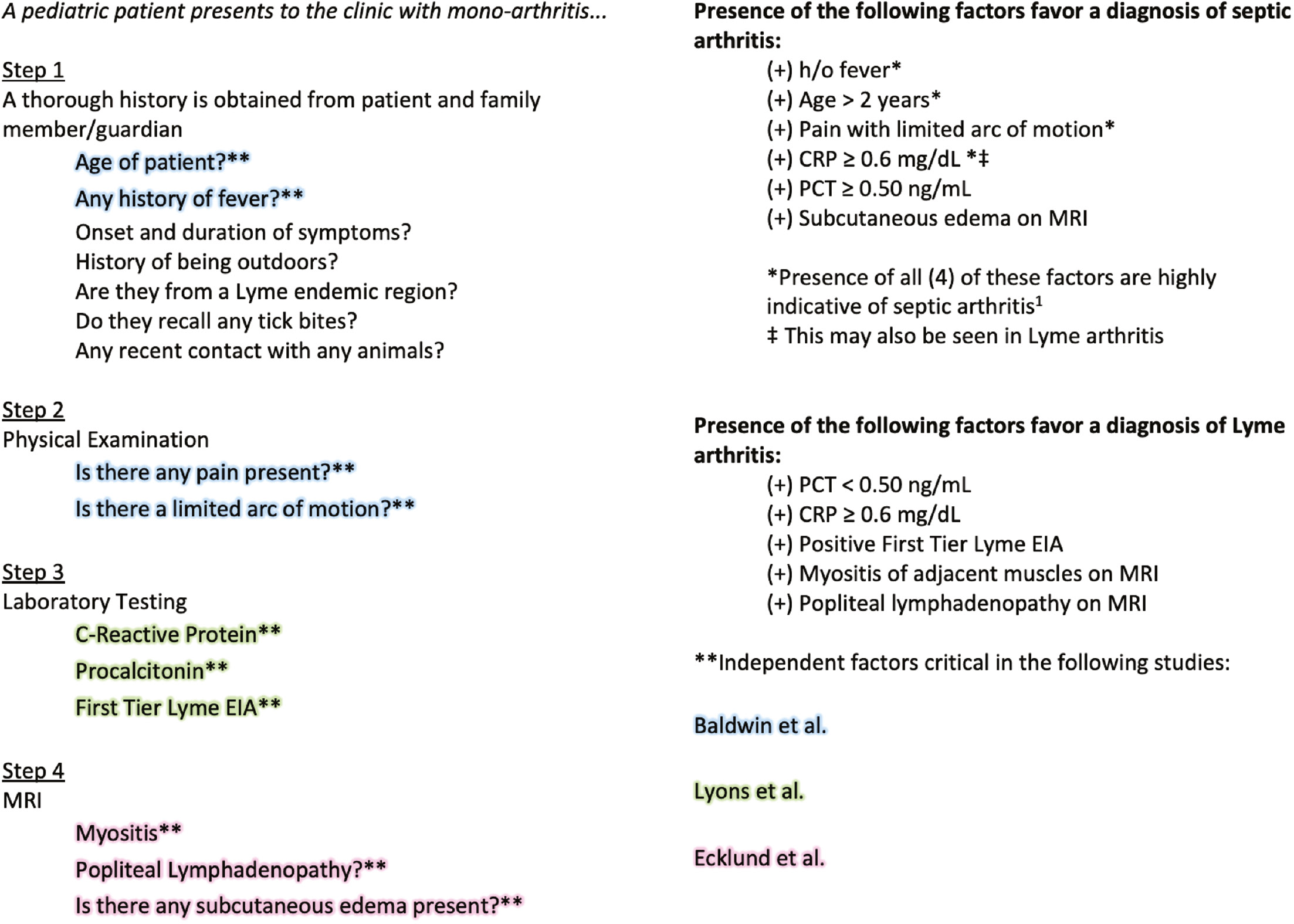

Baldwin et al.15 proposed a model to help guide the clinician in differentiating between septic arthritis and Lyme arthritis in the knee in the pediatric population. The model is based on four independent presenting factors that could suggest septic arthritis:

- The presence of pain and short arc of motion in the affected joint

- History of fever reported by the patient or a family member

- C-reactive protein of >4 mg/L

- Age younger than 2 years

Results from this study showed that the presence of one or more of these factors increased the risk of septic arthritis. Results from this study showed that the risk of septic arthritis with none of these factors was 2%, (1) factor was 18%, (2) factors was 45%, (3) factors was 84%, and if all (4) factors were found, the data predicted a 100% risk of septic arthritis. On the contrary, the authors suggest that if a presenting patient is older than 2 years of age, without a history of fever or limitation of motion in the affected knee and has a CRP of less than 4 mg/L, then they may be safely observed in anticipation of Lyme serologic studies to confirm the diagnosis and avoid unnecessary surgical procedures or serial aspirations. This approach is not without limitations. For instance, the pain of the affected joint with a short arc of motion is largely subjective and difficult to measure. A clinician may rely on experience and other signs such as refusing to bear weight to help determine the degree to which this factor may be playing a role.

Another algorithm to differentiate bacterial musculoskeletal infection (MSKI) from Lyme was proposed by Lyons et al. 9 and includes the following serologic data:

- Procalcitonin (PCT) ≥ 0.50 ng/mL

- C-Reactive Protein ≥ 0.6 mg/dL

- First-tier Lyme Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) = NEGATIVE

Results suggest that if a child has a PCT ≥ 0.5 ng/mL, CRP ≥ 0.6 mg/dL, and a negative first-tier Lyme EIA, then they are at high risk for an MSKI. On the other hand, Lyons et al. found that 92% of patients were found to have a PCT < 0.50 ng/mL, a CRP ≥ 0.6 mg/dL, and a positive first-tier Lyme EIA, had Lyme arthritis, whereas none had an MSKI. The authors recognize that the proposed algorithm is currently applicable to areas that are endemic to Lyme disease. Additionally, a crucial component of the model depends on a clinic having ready access to a first-tier Lyme EIA, which may not always be the case.

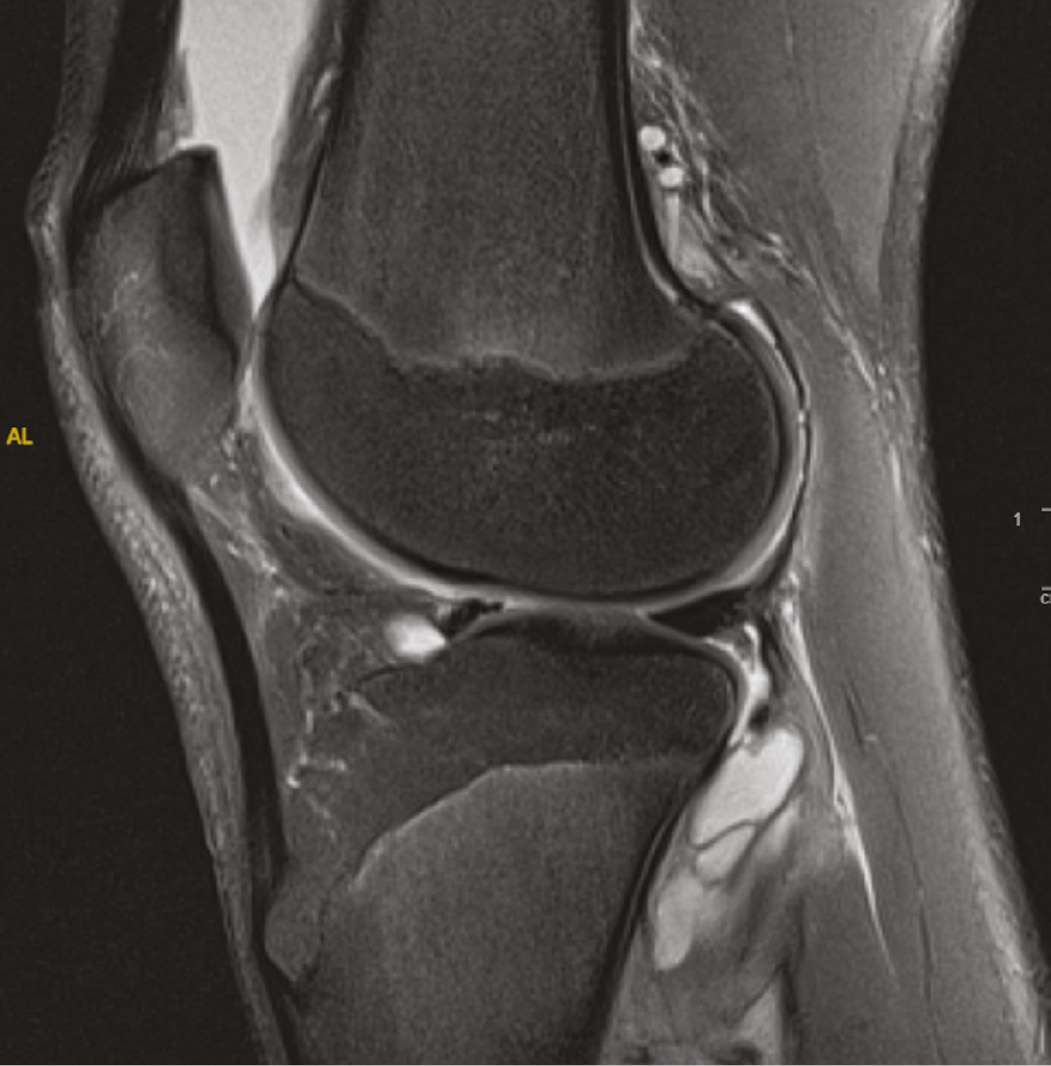

One study10 considered the MRI features that present in Lyme arthritis of the knee that may help guide clinicians in proper diagnosis. In comparing the MR images gathered from patients with confirmed cases of septic arthritis and Lyme arthritis, the authors concluded that the presence of the following three factors on MR images were statistically significant predictors of Lyme arthritis:

- Myositis in adjacent muscles (e.g., popliteus) (Figure 1)

- Popliteal lymphadenopathy (Figure 2)

- Lack of subcutaneous edema (Figure 3)

Figure 1. 15-year-old male with Lyme arthritis of left knee. Sagittal T2-weighted fat suppressed MRI revealing joint effusion, synovial thickening, and high-signal-intensity fluid within the popliteus muscle.

Figure 2. 15-year-old male with Lyme arthritis of left knee. Sagittal T2-weighted fat-suppressed MRI shows suprapatellar effusion, synovial hypertrophy, and popliteal lymphadenopathy.

Figure 3. 15-year-old male with Lyme arthritis of left knee. Axial T2-weighted fat-suppressed MRI showing large joint effusion, synovial thickening, and lack of edema within the subcutaneous tissues.

A lack of subcutaneous edema on MRI was the best independent predictor of Lyme arthritis versus septic arthritis, with a likelihood ratio test of 10.89, p <0.001.

Synthesizing Approaches

The following table summarizes an approach to differentiating between septic arthritis and Lyme arthritis in a pediatric population (Table 1).

Table 1. Synthesis of Independent Factors Utilized in Differentiating Between Septic Versus Lyme Arthritis

|

Conclusion

The importance of accurately and effectively differentiating between septic arthritis and Lyme arthritis in the pediatric population is critical. Although the two conditions may present similarly, septic arthritis may require surgical intervention, whereas Lyme arthritis may be treated effectively with antibiotic therapy alone. By synthesizing the proposed algorithms along with the incorporation of MRI imaging, a clinician would be better equipped to make an effective diagnosis while avoiding invasive procedures such as joint aspiration.

Disclaimer

No funding was received. The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

References

- Montgomery NI, Epps HR. Pediatric septic arthritis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2017;48(2):209-216.

- Daikh BE, Emerson FE, Smith RP, et al. Lyme arthritis: a comparison of presentation, synovial fluid analysis, and treatment course in children and adults. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(12):1986-1990.

- Arvikar SL, Steere AC. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(2):269-280.

- Cruz AI, Jr., Anari JB, Ramirez JM, et al. Distinguishing pediatric lyme arthritis of the hip from transient synovitis and acute bacterial septic arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus. 2018;10(1):e2112.

- Paakkonen M, Peltola H. Treatment of acute septic arthritis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(6):684-685.

- Dhanoa A, Singh VA, Mansor A, et al. Acute haematogenous community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis in an adult: case report and review of literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:270.

- Wall C, Donnan L. Septic arthritis in children. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44(4):213-215.

- Ross JJ. Septic arthritis of native joints. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31(2):203-218.

- Lyons TW, Kharbanda AB, Thompson AD, et al. A clinical prediction rule for bacterial musculoskeletal infections in children with monoarthritis in lyme endemic regions. Ann Emerg Med. 2022;80:225-234.

- Ecklund K, Vargas S, Zurakowski D, Sundel RP. MRI features of Lyme arthritis in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(6):1904-1909.

- Brown DW, Sheffer BW. Pediatric septic arthritis: an update. Orthop Clin North Am. 2019;50(4):461-470.

- Marcelis S, Vanhoenacker F. Lyme disease: a probably underdiagnosed cause of mono-arthritis. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2021;105(1):80.

- McCollough M. RMSF and Serious Tick-Borne Illnesses (Lyme, Ehrlichiosis, Babesiosis and Tick Paralysis). In: Emily Rose MD, ed. Life-Threatening Rashes. Cham: Springer; 2018:215-240.

- Talagrand-Reboul E, Raffetin A, Zachary P, et al. Immunoserological diagnosis of human borrelioses: current knowledge and perspectives. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:241.

- Baldwin KD, Brusalis CM, Nduaguba AM, Sankar WN. Predictive factors for differentiating between septic arthritis and lyme disease of the knee in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(9):721-728.